Thursday 21/01/2021

Smyrne to Lageia, Cyprus

The 106 year Journey

In the tiny village of Lageia on the foothills of the Troodos mountain range there is a small restaurant where you will often find Soutzoukakia Smyrne-ika. These are a particular type of meatball containing abundant garlic and cumin and cooked in a tomato sauce.

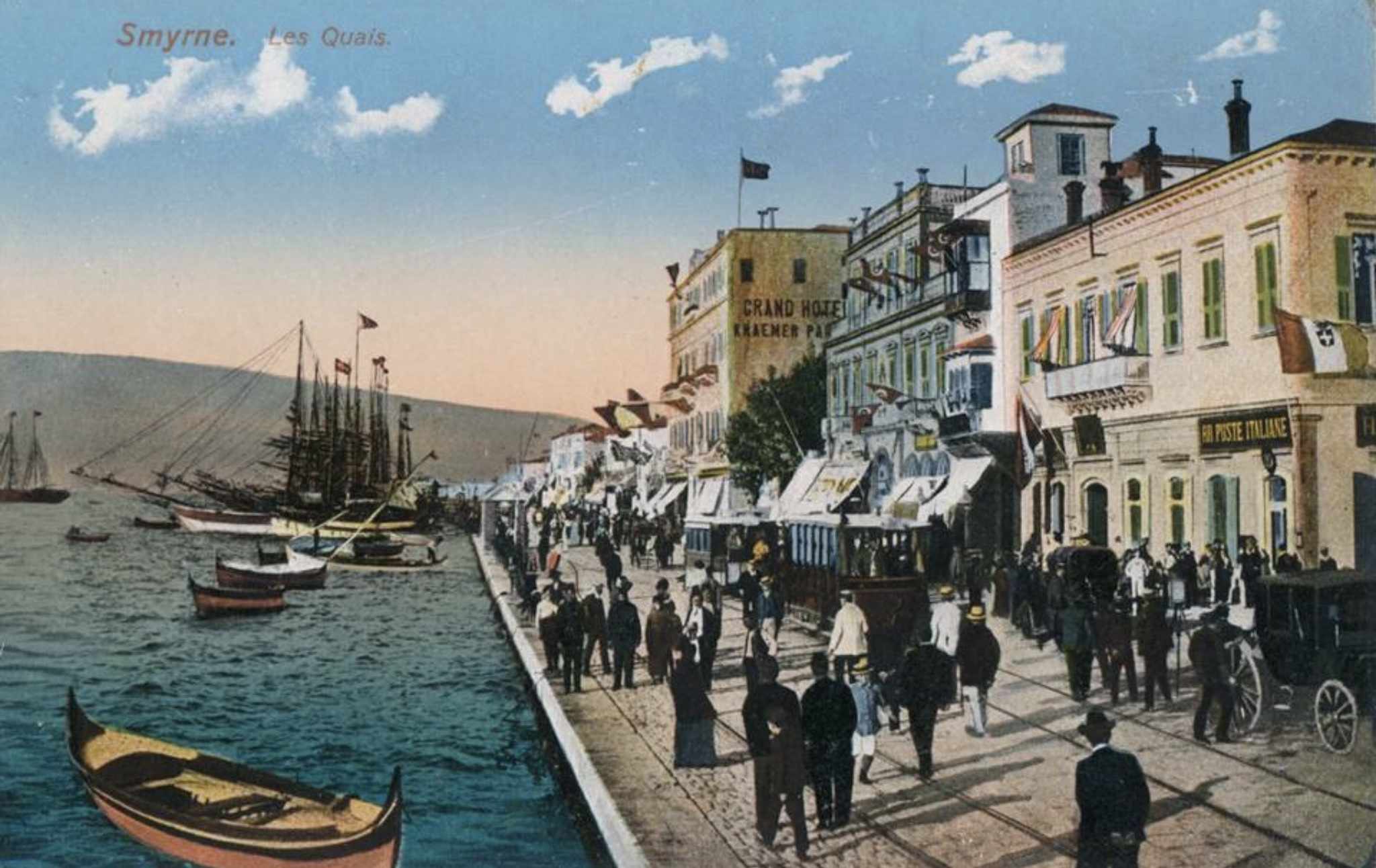

The dish originates from Smyrne, once a hive of culture and business and learning. This came to an abrupt stop in 1922 with what is known throughout the Greek Diaspora as the “Big Catastrophe”. It was one place where the Greek struggle for independence was not successful. The Greek quarters were burned down and tens of thousands of people were killed in barbaric ways over a few days. There followed an exchange of populations with the treaty of Lausanne in 1923. Refugees poured into Greece and with them they brought their traditional dish which was much loved and widely adopted by the Greeks.

My observation is that it does not have the same popularity with the Cypriots who generally seem to prefer chunky meat such as Souvla and Souvlaki. However, “Elladites” or “Kalamarades” (Greeks from Greece) whether on holiday or living permanently in Cyprus, as well as many foreigners, are enthralled to have the chance to eat their Soutzoukakia Smyrne-ika, so rarely found on this island.

The restaurant in question is the Kafestiatorion Lagias. It is run by the author of this article (Bill Warry) – an Anglo Greek (English father, Greek mother - her mother was from Smyrne).

Bill’s Yiayia was a teacher.The Turks had a policy of not allowing an adequate number of Greek schools. She and one of her sisters travelled by donkey to the various villages round Smyrne to teach Greek to the Greek children. They would meet at an appointed room and in winter each child had to bring a log. The eldest child in the class would light the fire. That was one of the stories about Yiayia that I remember being told by my mother (I will switch to writing in the first person person for the remainder of my narrative).

Another story was that somehow it fell upon the sisters to bring water from the well. One day for some reason none of them could carry out water-fetching duties and Great Grandfather Nicolas had to bring it! “That was really back-breaking,” said Great Grandfather Nicolas.

“What about us?” cried out the sisters. “We bring the water every day.”

"Why didn’t you say anything?” asked Great Grandfather.

"Because you wouldn’t have listened,” came the reply.

A week later a pump was in place by the well.

Way before the Big Catastrophe, life was getting increasingly hard for non moslems. One day Great Grandfather had gone to Constantinople on business.

“Mr Constantinidi - What are you doing here?” shouted Turkish friends. “Don’t you know that the Armenians are going to be massacred today?” This was way before the major massacre of the Armenians.

“But I am not Armenian, I am Greek,” protested Great Grandfather.

“Greek, Armenian… Who will know the difference? Go home quickly!”

Great Grandfather owned a silkworm farm. Once, so the family story goes, he had to go away several days to the mountains, I think to seek more white mulberry trees on which silkworms grow. He charged his Turkish foreman with protecting the family in his absence.

“Afendi,” said the foreman. I will put my bed across the door and sleep there. Only over my dead body will anyone come to harm your family.” I always remember this story when thoughts of ethnic bitterness come to mind.

Life, though, got increasingly difficult under Ottoman rule. Non-Muslims had extra taxes to pay. In court the word of a Muslim always took precedence over the word of a non-Muslim. Other injustices are pretty widely known. When Great Grandfather died, the family decided that life in their lovely land was too hard and precarious and decided to try to find work in Egypt. One of Yiayia’s sisters, also a teacher volunteered to go on an exploratory mission.

On the ship to Egypt, Great Aunt Clio met a Greek Orthodox priest who said to her, “Despinis (Miss) – What is a young lady like you doing alone on a ship bound for Egypt?”. She told him her story and about how hard life was becoming in Smyrne.

“I will help you,” said the priest, “I will introduce you to Greek families that would like private tuition in Greek. Now your other sister, she is a seamstress you say. Her first job will be to sew the Patriarch’s new vestments.”

When she heard this, Great Aunt Sofia was frightened. “But I have never sewn ecclesiastical vestments before”. The two teacher sisters rounded on her: “You know how to sew. You’ll manage”. So the family moved to Cairo in 1913 and had the good fortune not to be living in Smyrne at the time of the Big Catastrophe. The Greek lessons were in demand and after a while the two teacher sisters founded a small Greek school in Cairo. Yiayia married a Greek from Volos. The latter died when my mother was two. So I never got to hear of any family stories from Volos. But Smyrnan tradition, specially with regards to food remained firmly with us throughout my childhood. We regularly ate Soutzoukakia Smyrne-ika and other Asia Minor specialities like Adzem Pilafi.

I’ll cut now to my father’s story. He was English – a classics scholar who had graduated at the University of Cambridge. When he was a young man my English Grandmother had said to him, “ If you don’t drink any alcohol by the time you are twenty one I will give you £50 and if you don’t smoke by the time you are twenty one I will give you £50 for that. Well he did not make it for the alcohol challenge, but he did for the smoking one, so he claimed his £50 from his mother.

“What are you going to do with all that money?” she asked. It was quite a lot then.

“I am going to go on a historical cruise to Greece,” he said.

Already a classics graduate and knowledgeable of Greece’s past, he was enraptured with Greece. He decided to go and live on the island of Siros, writing short stories for a living. There was quite a demand at that time from English newspapers and magazines. Every time he thought that money was running out and that he would have to go back to England and do a proper job, another story would be published and he would receive another £6 which would cover another month’s living expenses in Greece. With his existing knowledge of Classical Greek, he quickly developed a fluency in Modern Greek.

Then World War II broke out. When he enlisted he told the army of his ability to speak Greek and suggested that they send him with the Greek allies. The army was a bit slow on the uptake and sent him instead to break German codes in North Africa. Towards the end of the war they sent him with the Greeks where he had a kind of liaison officer role. He became good pals with my future uncle, Nicolas, who had a similar role on the Greek side.

All the fighting had stopped. It was Christmas and my uncle said, “What are you doing for Christmas John?”

“Well, I’ll stay here. I can’t very well go to England.”

“Come to Egypt with me and meet my family.” And that is when he first met my mother. A few years later after lengthy correspondence and visits they married. He found work as a lecturer at the university of Alexandria and in 1947 I came along into this world.

We lived most of my childhood in the Middle East: Egypt, Cyprus and Libya where my father was Assistant Professor of English at the University of Benghazi. Libya was quite a nice country till the Western Powers destroyed it. My mother was an excellent cook and throughout my childhood I was nourished on a delicious diet of Greek meals including the traditional Smyrnan foods like Soutzoukakia Smyrne-ika and Adzem Pilafi that she had learned from my Yiayia and her Yiayia. The Adzem Pilafi has not been widely adopted in Greece, but the Soutzoukakia certainly have. I was a gastronome from a very early age. I remember my mother commenting that both my sister and I kept asking her how she had cooked this, what herbs she had added to that?

When I was fourteen we went to England for my better education and that of my sister. In Libya I went to the British Army school for a social life, but the standard was low and most of my learning was at home.

In England I graduated with a language degree. I always wanted to live in a Greek place, but there were always obstacles in the way. Eventually I made a leap in the dark and came to live in Cyprus about twelve years ago. Why Cyprus and not Greece? Like many Greeks coming to work here, I felt it had the same basic culture, but a slightly better economy. In 2019, a friend told me about the Kafestiatorion Lagias being empty and that the community council was looking for offers from someone to rent it and run it. I hesitated because it was far from the Paralimni area where I lived. However, I liked the idea of running a little traditional restaurant in the mountains. I took the plunge and on the 14th of August 2019 I opened up.

And that my friends is how 106 years after my Yiayia left Smyrne (taking her native cuisine with her), sometimes, as dish of the day in a tiny restaurant in a tiny village in the foothills of Troodos, you can find a number of traditional Smyrnan dishes like Soutzoukakia Smyrne-ika and Adzem Pilafi, recipes that I have learned not from a cookery book, but from my mother who learned them from her mother who in turn learned them from her mother in Smyrne.

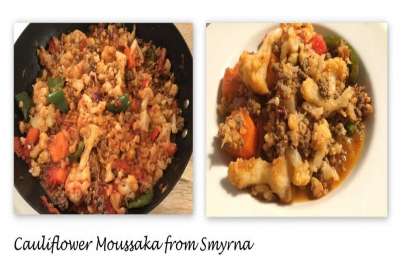

If you liked this article you might like to read how moussaka was made in Smyrne in the early 20th century

English

English

Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά Русский

Русский

Posted by

Bill Warry

Posted by

Bill Warry